“Mattie once asked me how you know when you like someone, and if I liked any boys like she did, and I didn’t know what to tell her. That I tried not to think about that kind of stuff, because it was painful, because I thought I could never have it, but when I did end up liking someone, it always made me ache right down to my core. I realized pretty early on that the who didn’t really matter so much.”

Sadie

10.

There’s something about a queer life in retrospect—all those pieces suddenly, shockingly, fitting into place.

While writing my sixth novel, Sadie, I decided the titular character was someone who wasn’t exactly sure how to label herself, but knew, implicitly, she wasn’t straight. That could be me, I thought, writing it—or could it?

No, I decided.

No, because being gay seemed like it should have a level of urgency attached, and there was nothing so urgently felt here. Not in the question turning endlessly round in my mind long after it met my supposed answer and the book had been handed in. Not after it was published, my heart all aflutter when queer readers recognized it as a queer. Not in my hurt at being left out of my publisher’s featured book lists during Pride. Not during the moment I recounted Portrait of a Lady on Fire to my mother, only to stop halfway through my retelling to cry. (“It was just a really sad movie.”) And not in anything that long preceded all of this—my intense interest in queer media as a teen, the Pride Parade I insisted on attending then too.

The feelings I had for certain girls.

It can’t be a closet, I reasoned, if there’s room enough for you to move comfortably within it. It can’t be a closet if, the whole time you’re in there, you can breathe.

And so, in that absence of urgency, nothing queer—

Only true heterosexual allyship.

My eighth novel, I’m the Girl, is based loosely on the Jeffrey Epstein case and follows Georgia Avis, a sixteen-year-old lesbian determined to prove her worth and escape poverty by securing a job at Aspera, an exclusive, members-only resort known for hiring pretty young things—“Aspera girls”—to cater to the nation’s elite. Georgia is a dreamer with big plans for herself who is acutely aware of the limits her circumstances place upon her future. Her beauty comes as a great relief. She knows her body, which she describes as “perfect” throughout, offers her her greatest chance at being hired.

On her way to the resort to plead her case, Georgia discovers the dead and brutalized body of a 13-year-old girl, Ashley. In teaming up with Ashley’s older sister, Nora, to find and bring Ashley’s killer to justice, Georgia becomes an Aspera girl, and is thrown into a seedy world of unfathomable privilege and wealth.

I’m the Girl is less a thriller than it is a pressing portrait of our world through the eyes of a girl groomed into believing her beauty affords her a level of sexual agency and control over the increasingly dangerous situations she finds herself in. Georgia is conditioned into enjoying the “power” she holds over the men she encounters to the point she is unable to recognize their abuses of her body. (“When a man looks at you the way [he] looked at me . . . there’s nothing he can do to you or force you to do.”) This culminates in one of the novel’s most unsettling and heartbreaking sequences, wherein Georgia’s consent is expertly weaponized against her by way of her sexuality. Just before Matthew, the Epstein avatar, rapes Georgia—who is under threat of being fired for being too beautiful for him to resist—Georgia assures him his actions won’t mean anything, can’t mean anything, because she likes girls. What is on trial in this scene is Georgia’s abuser, not her sexuality, and it demands the reader recognize this. More, it demands the reader recognize that Georgia will not, because she cannot, because this is how grooming works. It’s successful because of the misogynistic, classist, and patriarchal culture the story is based on—the same culture that enabled Epstein’s atrocities for years and repeatedly silenced the voices of the girls he hurt.

The patriarchy works to deny us access to the parts of ourselves that don’t conform. At times, its manipulations, its rewards and punishments for falling in or outside of its lines, can be so painfully obvious we don’t accept the ‘failure’ of its victims to see them, which is another way it keeps us complicit in upholding it. I’ve made a career writing novels that critique these constructs, so much so I thought I could spot them miles away. Yet I remember spinning Georgia from thin air, a girl who fell to pieces at the sight of other girls and wasn’t afraid to relish in it, and how I’m the Girl’s sentence-by-sentence development gave way to a rising—and urgent—panic that had me begging my friends to tell me I was too straight to write it.

9.

Early 2020—the brink of the pandemic.

I watched the entirety of Natalie Wynne’s coming out video, Shame, struggling not to relate to some of the things she said in any particularly gay way, then opened up the Am I a Lesbian? Masterdoc linked in the video’s description in hopes of finding something even less relatable there. I could barely glance at its table of contents—What is Compulsory Heterosexuality? How do I know if I’m a Lesbian? But I like Fictional men/male celebrities—before quickly directing my cursor, by way of my trembling hand, to the x in the corner of my browser.

By the end of June of that same year, I decided to make a greater commitment to straight allyship and requested Sadie be included in my publisher’s Pride stacks. I knew Sadie’s queerness meant something to queer readers when they discovered it so why not finally signal the book was there for them? Sadie’s sexuality being a feature, and not the point, was the agreed upon reason for past oversights and its future potential in these spaces was noted.

The feature, not the point.

What of its fact?

8.

In 2021, JoJo Siwa’s coming out had me sometimes daydreaming about a soft reveal, like wearing the gal pal pin I’d furtively ordered online (and hid in my desk) in one selfie or other, declaring my truth without ever having to verbalize it. The only problem was I hadn’t yet convinced myself it was true and there was a difference between choosing not to say something and being unable to. I couldn’t imagine myself a part of the queer book community, where I felt so outside its abundance of joy and pride. I didn’t know where my pain and uncertainty fit, and to my mind, it only exacerbated the probability I couldn’t be queer.

Once, when I was marveling over my circuitous path to what some felt was its least surprising conclusion, one of my closest friends, D, who is also a lesbian and watched this play out, said to me, “You can’t tell people about themselves.”

But this was what I wished for most. I wanted someone, anyone, to settle this thing inside me and if it was there, to see it without my prompting—so that I could take a closer look. Though I couldn’t directly face it then, it was one reason so much hinged on Sadie’s recognition as queer. What was seen in her could maybe be seen through her, to me, and in that, my answer. That it was never consistently acknowledged was a game of chicken I needed someone to tell me I could stop playing with myself: if it is, maybe I can be. If it’s not, neither am I.

The more I immersed myself in I’m the Girl’s queerness, and the way it made me feel when I did—apprehensive, upset—the more I suspected I was not, in fact, a heterosexual ally. I was a heterosexual mercenary trying to talk myself into being gay just so I could get away with writing and selling a book about a character who was.

If that was the case, I should stop.

If that was the case, I needed to stop.

So why couldn’t I stop.

What if—

What if, I thought.

What if I tested the waters, just enough to maybe free my mind.

Your girl’s not straight is how I informed my closest friends. I remember every single instance of this admission; a fist closing around my heart. Unfortunately, I did not feel freer, and thereby gayer, for it—I worried even more that I was a fraud. Maybe that had something to do with my careful, almost non-committal framing, that, when spoken aloud, held the upward curve of its invisible question mark.

Also, the use of third person.

Amid all this, I got my wish: a friend of mine, also a lesbian, M, asked D if I was gay because how couldn’t I be?

I was elated—

“What should I tell her?” D asked me.

—but immediately paralyzed by the thought that I would be lying if I said I was. Heterosexuality felt like an inevitable, inescapable truth of myself, patiently waiting on my horizon, and my fear forced me to make space to meet it there, leaving no room for me to wholly embrace the alternative.

“That I’m figuring it out,” I answered.

I remember laying in bed that night, reliving the exchange.

Peering inside myself, peering out.

I’m the Girl progressed and the more it progressed, the gayer it got. I worked my way through the stolen glances and almost-kisses, then definitely-kisses of the two girls at its center and by Spring 2021, it had so queerly asserted itself, I was asked by my publisher how they should approach marketing its gay content and how they should answer the question of Courtney Summers writing a gay book. It was nothing that had to be decided in that moment, considering the manuscript wasn’t done, but with June nearing, I returned to the possibility of Sadie being included in Pride round-ups, which would remind readers I’d written a well-received queer character before. I was not ready to come out, and as such, willing to let I’m the Girl speak for itself. But as I later wrote in a newsletter approved by my publisher, this would become a question of Sadie being a queer book and how, then, would they answer?

If Sadie was queer, how was it a question?

Because we’ve left it out for so long.

Because there was no queer romance in its pages.

My publisher was concerned they would look opportunistic by suddenly including Sadie in their Pride lists so many years after release, given the book did not contain a romance or identity-led (coming out) arc. Feature. Point. Fact. I remember the hot flush of shame across my skin as I was told this, and it led me to out myself as queer, for the first time, to my publisher. While the news was warmly and supportively received—and that meant something to me—I was left to grapple with a worsening sense of discomfort in that conversation’s wake. Rather than further interrogate what qualifies a book as queer, I was vulnerable enough to let it reinforce my fears.

If a book with a queer protagonist who knew about herself better than I did wasn’t queer enough to be celebrated, then what did that really make me?

Regardless of their approach, my publisher would not be able to prevent I’m the Girl from being de-emphasized or excluded in other queer spaces if I chose not to disclose. After further talks, we settled on Sadie being a part of their upcoming Pride posts, but as the appearance of opportunism was still very much a concern, personal context would be helpful. Now or later? was the question that seemed carefully and indirectly posed to me. I wasn’t ready, but I knew this much: I wanted every opportunity for I’m the Girl to succeed for the book that it was, and Sadie’s omission from these spaces hurt in such a way that going through it again felt untenable. I didn’t want conversations about the book to shift from what was on the page to what wasn’t at the story’s expense. Whether or not I could ever convince myself I belonged in queer spaces, I’m the Girl did.

And so, ready or not—

I wanted badly to reach out to M and ask her what, exactly, it was about me she thought was so gay but that seemed like a weird thing that no one who was actually gay would do.

7.

My publisher helped me prepare for my outing never knowing the full extent of my unease. I don’t want to do this, I’d tell my agent privately while returning to group emails to finalize the particulars with exclamation-marked aplomb: Let’s do this!!!!

I was not trying to deceive them; it’s always been important to me to meet their enthusiasm and hard work with my own, and I wanted them to know I recognized their efforts here. I worried any reservations might leave them feeling undermined and unappreciated.

This contradiction also—and in a way that amuses me now—served as a kind of anchor. Recognizing, appreciating, and bestowing allyship consoled me because they were actions I could clearly define doing as gay.

There’s this scene in Sadie when she’s tired and hurting and finds herself in the company of another girl . . . Just before they kiss, [she] has a revelation. It’s not that she’s queer—she’s always known this—it’s that after a lifetime of being forced to put her sister first, she wants to own the desire within, and only, for herself, I wrote in a June 2021 Instagram post my publisher would go on to quote in a Pride-themed newsletter including Sadie for the first time. Sometimes a book walks a line between what its author wants to tell you and what they hope you’ll see. I remember writing that scene with my heart in my throat; putting a toe in an ocean I could give someone else’s name. And how I felt, how I still feel—and what it gives to me—when someone Sees it.

‘It.’

I was met with a flurry of support, and though I was uncomfortable with the attention, I was overwhelmed and gratified by the love that drove it. A collective of people finally seeing me. I want to be able to say this was the moment I let everything go and let something beautiful and essential about myself in, that all questions disappear in the face of other people’s acceptance, but my friend D was right: you really can’t tell people about themselves.

When one of the most private parts of your life is imposed upon by your profession, you might convince yourself it’s a fair cost of doing business, especially a business in which you ultimately have very little control. However well-intentioned, the resultant trauma of that imposition—not all of which has been or can be expressed here—was more than I was, or could have been, prepared for. It was very hard to accept as a defining part of such a deeply intimate journey. In its immediate aftermath, I didn’t feel closer to greater certainty than I did to certain shame. I had performed an idea of myself that did not exist, and consequently had no idea how to live up to, with only myself to blame. My friends were quick to point out that while I might have been responsible for my choices, it did not rend the circumstances under which I made them, and how they were presented to me, above or beyond scrutiny. But I didn’t have the capacity to do that; I still had a book to finish.

I do not recommend tying your incredibly fragile sense of identity and validity as a queer person to your career, and I especially do not recommend doing this on a deadline.

6.

I’m the Girl was one of the most demanding novels I’ve ever written. Its horrific subject matter and the amount and intensity of the research it required broke something in me I would later realize was compounded by the stress of what came before it. I worked myself into a state of such mental, emotional, and physical fatigue that I didn’t have the energy to continue litigating my sexuality. This, it turned out, was a blessing in disguise. In that place of lessened defenses, Georgia’s story whispered something to me I could now put myself on the path to understanding.

Queer community is vital. One of the greatest gifts my small and beautiful group of queer friends gave me was the freedom to witness them as they so fully embodied themselves, to listen to their vibrant discussions about identity, history, and found family. I wanted to learn, to participate, to form opinions of my own. I bought a copy of Never Going Back: A History of Queer Activism in Canada by Tom Warner. Its earliest pages delved into the patriarchy’s role in various oppressions and there was that term I’d heard and seen before: compulsory heterosexuality.

Per Wikipedia, Compulsory heterosexuality (often shortened to comphet) is the theory that heterosexuality is assumed and enforced upon women by a patriarchal and heteronormative society. The term was popularized by Adrienne Rich in her 1980 essay titled, “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence.” According to Rich’s theory, women in every culture are believed to have an innate preference for relationships with men, and this leads women to devalue and minimize the importance of their relationships with other women—

Oh, I thought.

I revisited the Am I a Lesbian? Masterdoc in the company of some of my closest friends. We went down its list together.

And I saw myself.

I was raised in a heterosexual household, surrounded by people who could live comfortably under the umbrella of cis-heteronormativity. The women in my family married men, and married young, most when they were still in or just out of high school. I’d let those seasons of my life pass without managing to do the same. It was a concern of my paternal grandmother’s, who would regularly question my lack.

At twenty-two, I signed my first publishing contract for my debut novel, and I was determined to be signing publishing contracts for all my days to come. This was not enough to assure Grandma of my future. I needed a man. Her vision for me made a cold sweat break out on the back of my neck and turned my stomach to acid. I thought this anxiety stemmed from my failure, that I was running out of time to be some good man’s good wife. Now, I finally recognized its true source: it was the possibility of becoming some good man’s good wife. Marriage to a man was a circumstance I could only contemplate in terms of enduring, in terms of arrangements that might make it barely tolerable. He should be at work. Forever. Could we live in different houses? As my grandmother’s insistences became increasingly upsetting to me for reasons I couldn’t articulate, my father finally intervened, asking her to consider the fact my career was my priority.

This she understood. Women were never meant to have it all. A career or a man. A career or babies. If my heart was set on being a successful author, there was no reason to believe I could have any of the rest, so she could let the rest go.

And so, to my relief, could I.

What’s more—here was a way I could fit. I could take these inexplicable pieces of me, the ones that could not name the love they wanted, and force them into a shape that felt convincingly status quo because no matter what I couldn’t admit to myself at that time, I knew on a fundamental level there were less complications and more rewards for me if I turned my back on it.

I walked into that chapter of my life with no question of the fact I could be straight.

This level of repression is so strange. Its function of denying you the language of yourself, in turn, invents a whole new language. This language makes no fucking sense and perfect fucking sense at the same fucking time.

I wasn’t gay—I was a professional.

It still stuns me how entirely absent the word ‘queer’ was from my personal vocabulary. I was that author whose work regularly seeks to confront the cis-heteropatriarchy’s manipulations, but had not at all managed to escape them. What is so obvious to me now was so invisible to me then, but it seems appropriate that one of the very same things I hid behind—my career in writing—ultimately began the painstaking process of pushing back.

When I returned to I’m the Girl, a story so informed by similar manipulations, I clearly saw its underpinnings, clearly saw the contents of my own heart hidden in someone else’s journey until the moment I could confront it in mine.

All those pieces suddenly fitting into place.

5.

After Georgia is raped by Matthew, she has consensual sex with Nora, the girl she’s fallen for. Their sex scene is intentionally blocked in a slightly similar way, but subverted in how Georgia responds to Nora, in how she feels about Nora, in how she receives Nora’s every touch. With Nora, Georgia is safe, loved, and respected. It’s Georgia’s first inkling of the difference, and it leaves her shaken.

“Aidan Archer was my first kiss,” I say.

“When he got you drunk?”

. . .

“He kissed me.” I make myself look at her. “And it was the first time I was ever kissed.”

And if that’s not a kiss, what else do you call it?

At the end of I’m the Girl, Georgia realizes she’s been abused by a system she, a sixteen-year-old girl, is helpless to fight. If there’s a point in her future where she decides to, as so many of Epstein’s survivors later did, it all comes down to this moment in her present, where she has a choice: accept the (lack of) value Aspera has placed on her body and all it has to offer her, or reject this and begin the process of healing, and believing she deserves better—and is worth so much more.

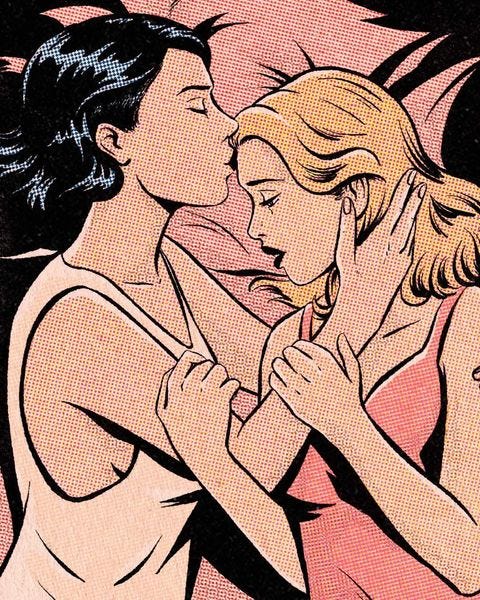

It is Nora’s hands against Georgia’s face, seeing her and telling her so, that empowers Georgia to step outside of the patriarchy’s lines and begin the process of reclaiming herself. Her identity as a lesbian is significant piece of that reclamation.

When you consider the scope of what she was up against, it’s not a small victory. It’s the kind of victory you can build upon, that might, over time, encourage you to speak your truth, assemble an army to return with, and demand justice. I believe in Georgia. I consider it one of the most hopeful endings I’ve ever written.

I didn’t want it to feel so personal when the integrity of the book’s lesbian representation was called into question by early readers who identified as gatekeepers, and who I suspected identified as allies, but having to negotiate Sadie and I’m the Girl’s positioning with my personal life made it feel, well—personal.

How could Georgia be a lesbian if she cared about what men thought? And what’s more, caring about men, to the extent she wielded the “power” she had over them with her body made it easier to label her a willing participant of her own abuse than it did a lesbian. The queer romance, then, could only feel tacked on and gratuitous, male gazey, written by someone—straight.

What makes a book queer?

Sadie’s initial exclusion from Pride was attributed, primarily, to the book not having a romantic or identity-led arc, and it was hard not to notice the ease with which those types of books seemed to be delivered to and beyond their intended audience. I wasn’t convinced this was only due to the accessibility of their subject matter, because I’ve always written dark and challenging books that ended up in the hands of those who needed them. When I suggested we include messaging that leaned on the tropier aspects of George and Nora’s relationship in service of that, it was suggested back to me this would be dishonest. But when I’m the Girl ultimately did manage to reach the readers it was especially meant for, they connected not only with those aspects of Georgia and Nora’s relationship, but to Georgia’s lesbianism, and its significance to the plot in precisely the way I’d hoped. I was not interested in defending the book against its most homophobic takes, but if it didn’t find the homosexuals, what choice did I have? I seemed to be having a problem consistently reaching queer readers and it was starting to feel like that reach was contingent on first writing a book that was more easily categorized as gay to people who weren’t.

And if that was the case, who had I come out for, and why?

4.

Community-led discussions—particularly backlash—about queer representation has resulted in an industry that’s adopted a self-protective strategy of response that can make authors feel pressure to disclose. I don’t think this strategy is conducive to serving queer authors, books, or readers, I said in an interview with GO Magazine. [T]his isn’t an indictment of the hard-working people behind the scenes, but illustrative of what a difficult space it is to occupy and satisfy [ . . . ] it took a while for talks [with my publishing team] pertaining to the lesbianism in “I’m the Girl” to feel truly productive, as oftentimes we weren’t talking about it—we were talking about me, my queerness, and comfort levels in relation to it. I was too vulnerable, too freshly uncloseted, to effectively navigate many of those conversations the way I could now. I was desperate to minimize the potential for public scrutiny into my personal life but couldn’t do that without undercutting the very reason I’d come out in the first place—to speak freely about and position the book as a lesbian title [ . . . ] I’m glad we got there in the end [but] I had to first reach a place that enabled us to shift focus back to where it should have always been: the book.

In an attempt to reach queer readers more directly, I requested a meeting to address my concerns. That meeting stands out in my mind as the first time I explicitly self-identified as a lesbian to the team as a whole, and the first time I explained the significance of I’m the Girl’s lesbianism to them, because up to that point, I’d taken it for granted. Their responses confirmed this element of the book was not something it failed to express; I’m the Girl did relate a complex experience of being queer under patriarchy, but for some readers—particularly those who have not experienced that themselves—forming those connections was work they’d have to choose to do. Messaging that encouraged this was, and had always been, key.

We brainstormed ways to communicate the book more effectively to lesbians. Solutions included my decision to publicly identify as a lesbian (up until that point, I had only publicly identified as queer), revising the online copy, and crafting new, queer-centric letters to go out with finished book mailings.

I was uplifted, I told my agent afterward, by marketing and publicity’s receptivity, by their sensitivity, humor, and heart. It’s important to note my team had many unique considerations of their own to navigate, the stress of which can also take a toll, but they’d worked hard and with great care, and, most importantly, great empathy, in trying to do right by a situation that, however difficult, left me with greater knowledge and acceptance of myself. When these conversations are still so new and tender, they can be left to a dangerous type of silence, especially if—as was my situation—there are things you aren’t yet ready to say. Conversations like the one we’d had can only be productive if those involved approach them in good faith, without defensiveness, and with a willingness to learn.

With I’m the Girl so close to publication, it remained to be seen whether our attempt to course correct would provide more comfort than cure. I had done my best, now I could only hope for it.

3.

I think of myself as caught between my industry’s commitment to diversifying shelves and a gap in its vocabulary when it came to grasping the nuances and complexities that can define queer lives, which, of course, extends to the unique nuances and complexities that can define all marginalized lives.

In a profits-based business, we know the success of these books begets the acquisition of more, but to give them the best chance of that success, they can’t just be published—they must be understood. This can only be achieved through publishers diversifying their staff at every level of its workforce, hiring those in possession of these vocabularies, and offering them fair contracts, a livable wage, good benefits, job security, and clear paths for advancement. There is no part of my own experiences as an author, or the experiences of any other publishing professional, that would not be enriched by this—yet many of the people who long ago started and continue to lead these important conversations and demands for change take on high personal and professional risks in doing so.

The more expansive, inclusive, and diverse this industry’s workforce is, the more expansive their conversations about and approaches to diverse books become, which makes way for even greater opportunities for their authors to be heard—and for their audiences to be seen.

2.

“As a lesbian reader, I am so grateful for I’m the Girl as George’s story speaks truth to my own.”

1.

Sometime later, I told M how defining, how important the moment she asked whether I was queer was in my ongoing process of self-discovery. She told me she’d been speculating about me with her wife.

I wouldn’t want to imply it’s something we knew better than you, but like, the recognition was always there! Something in you and we knew it from something in us because it was the same sound, she wrote. The same GAY GOLD LIMNING.

I finally understood what really drove the fear that followed me after I let a certain closet door open just wide enough to glimpse the goodness beyond: it wasn't that I was afraid heterosexuality was an inevitable and inescapable truth of myself, patiently awaiting the moment I could no longer deny it. I was afraid that because I had lived so long and so easily in its lie, and lost so much to it, that it would one day find me again, and deny me my truth.

“There’s a chasm between knowing something and saying it out loud, and I’ve lived in the silence of myself for so long,” Georgia narrates, before she comes out to someone for the very first time. But Georgia knows who she is, has known who she is, and she isn’t ashamed to admit it.

That part, she tells us, is over.

Purchase I’m the Girl.

❤ thank you for being so honest and brave and putting your fears and confusion in to such important words❤ I really hope this need of certain members of society to have people outed to authenticate their art stops, it can be so traumatic and damaging. ☹ (I remember a female author a while ago being publicly forced to admit she was groomed and abused by a teacher just to validate her book to a society who demanded it ☹. It's so wrong.

Thank you for sharing. As a longtime fan of your work (I'm 25 and started reading your books when I was 13), and a person who has had my own struggles with finding peace with my identity - or at least how to name it - I hope you are able to continue to share your truth when and how you choose to share it. No more and no less.