Before he died, my grandfather told everyone at his church my first book might be made into a movie. No matter how much I insisted otherwise, he said it was not a lie because anything that might happen had a chance to be true. He didn’t live to see its release day and that book never made it to Hollywood, but in the time between its sale and his passing, he loved to entertain its wildest possibilities in the most unabashed way—no matter how hard I tried to discourage him.

Before she died, my grandmother told me my fourth book was definitely going to be a movie. It had to be. It had fallen into the hands of a director who connected deeply to its story and while he had an electric vision of it for the screen, some of my books had been optioned before and no matter how promising, nothing materialized. Still, this one will happen, she’d tell me. Well, I’d say. We’ll see.

Don’t get your hopes up. You hear it a lot in this industry. Common refrain. Such a long shot to get a book published, any potential turns of good fortune stemming from it are usually framed as even longer shots than that. Don’t get your hopes up, but how high is up, actually, and what’s the real harm in sending them there? Whether or not things turn out the way we hope they would is not the consequence of the belief they could. Hope, I think, is divorced from the ego and the entitlement that is sometimes—though not always—wound through expectation. Hope expects nothing, and dares to be vulnerable in its desires for self and others, regardless of the odds for or against it. I’ve often been afraid of that kind of surrender, but when my grandmother died, I thought of the experiences I’d deprived myself of because of this. Connecting through the genuine wish to see something good happen, to be sustained and buoyed by that generosity, its underpinnings of belief, and to recognize it in gratitude.

After she died, the momentum behind the movie in question continued to build, and there was her voice in my head: This one will happen. My grandfather’s, too. It has a chance to be true.

This is Not a Test is a special book to me. I was around twenty-five when I wrote it, and I was down about everything, a definining feature of the latter half of that decade. Fall for Anything had stretched me thin, and so much of what the story became was a response to that, to how I was feeling at the time. All of this generated a certain sensibility in my style that would be exactly what Sloane’s narrative required.

I wrote it, mostly, at my grandmother’s house, at the kitchen table in the late midnight hours. Back then, it was still heavy with the presence of my grandfather, who I missed terribly.

Most of the time, I felt like I wasn’t good enough to make a shift in my writing that allowed for zombies. I didn’t know how to make Courtney Summers and zombies work, and the manuscript would crumble under the strain of that fear. I had to start asking myself what it was about the idea that drew me to it up until the point I’d cave to my insecurities.

The first zombie movie I can remember seeing was Night of the Living Dead. I think I must have been eleven or so, I think it was on TVO or PBS around Halloween. I was captivated by its agonizing pace, the terrifying relentlessness of the dead, that tiny spark of hope that propelled its characters to their grisly end. Its cruelly indifferent conclusion felt like the deepest betrayal to me. It was beyond the comprehension of my child mind. I cried, I had nightmares, I was so disturbed, and I vowed to never watch it or anything like it again.

But for an author who has made a career of leaning into discomfort, I ultimately find it impossible to resist in all other art. And what I end up running from, I will always find my way back to. It ended up a bit of an obsession, Night of the Living Dead. I wanted to tear off my skin and see what, exactly, the movie had left underneath because I couldn’t stop thinking about it, and this was soon reflected in obsessive rewatchings of it, and the introduction of other zombie movies. I was as hungry for understanding as the dead were for the living. Zombies were a staple of my teens and twenties. Why did I want to spend so much of my time with those stories, and what was it about them that so spoke to me enough to think I could tell my own?

I eventually realized it was the way that everything was over and unending at the same time. The prospect of persisting in those circumstances. I thought, what would it take to want to survive something like that? Because that’s what felt like the lie. And then I thought, what if your survival turned out to be incidental, and what you’d really wanted was uniquely complicated by that cruel and indifferent reality in a very particular way? Slowly, the book began to take shape, and with the angling I’d arrived at, it was hard to imagine a Courtney Summers book that wouldn’t allow for zombies.

“It takes some artistic guts to set a portrayal of a suicidal teenager amid attacking zombies,” Kirkus wrote of it back then, “but Summers has a history of risky choices.“

This is Not a Test represents a transitional state in my writing and my personal life. Some of Sloane’s observations are startling in the way they reflect this, and could have only been conjured by a me in that moment, struggling through creative growing pains and the existential crises posed by everyone’s late twenties, while also caught between what were two monumentally transformative losses. That of my grandfather, which came years earlier, and was a long time raw, and one I could have never anticipated—my father. It was the last book I wrote while he was still alive and it published eight months after he died, after a brief but nightmareish battle with lung cancer. It is a book deeply imprinted with the shock of that loss, and the will it required of me to push through it. I’ve always loved and treasured it for the record it keeps between its lines of two very different kinds of survival—Sloane’s and mine.

I’ve gotten to read various versions of the script, which I’ve loved. The most recent involved a scene I hadn’t seen before and when I told Adam it was a very nice touch, he told me he’d tweaked something—a small but very specific detail so it was just like the book. It was a matter of a few words, but they were words that, without his knowing, I’d placed into the story all those years ago to honor my grandfather and grandmother. And though they won’t get to see it, they’ll get to be part of it—this wild and exciting turn they always told me would happen someday.

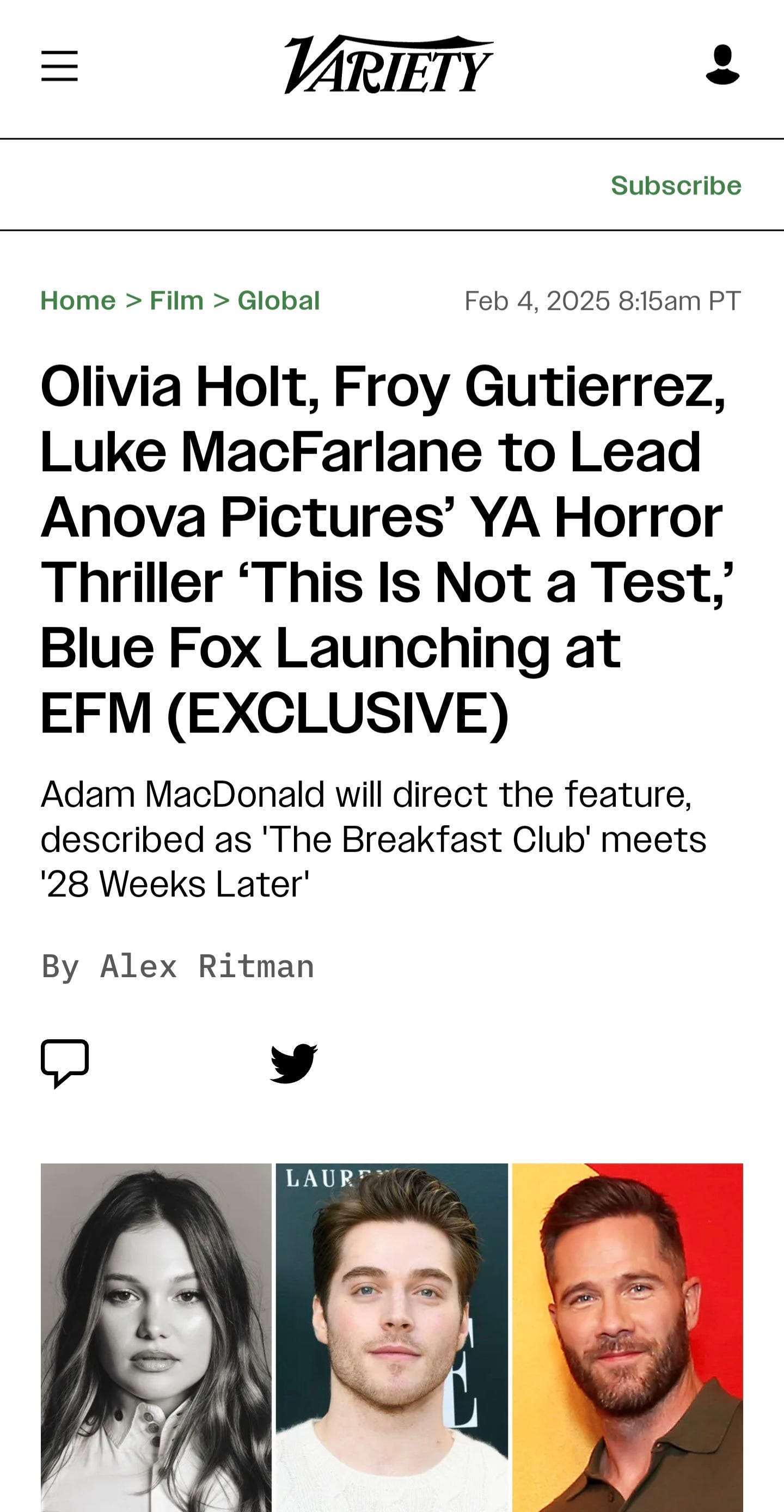

I’m grateful to the inimitably talented Adam Macdonald for believing in Sloane’s story and working tirelessly to make it happen, to Cybill Lui of Anova Pictures whose passion for and commitment to film has been integral to seeing this one through, to its extraordinary cast—Olivia, Froy, Luke and more!—for the life they will breathe into its characters and to Mary Pender, WME, CAA and Faye Bender at the Book Group for their stellar advocacy and support.

I’m especially grateful to all you readers who loved this book so hard, you let it take a bite out of you. Thank you. I love being able to share this with you.

explore my novels / support my work: courtneysummers.ca

instagram.com/summerscourtney

Congratulations! I am excited to read your new book. I value your input and your experiences and how you share this with all of us. I have purchased your previous books and follow you for your thoughts, the information you share, and the writers you support. Thank you for all that you do!!! As soon as I can I will order this new one.

NO WAY!! I've loved this book for years--it's my favourite of yours! This is such wonderful news. The 2010s were such an iconic era for zombie stories--I still have a zombie manuscript of my own from then kicking around in my laptop somewhere! I can't wait to hear more as the adaptation develops!